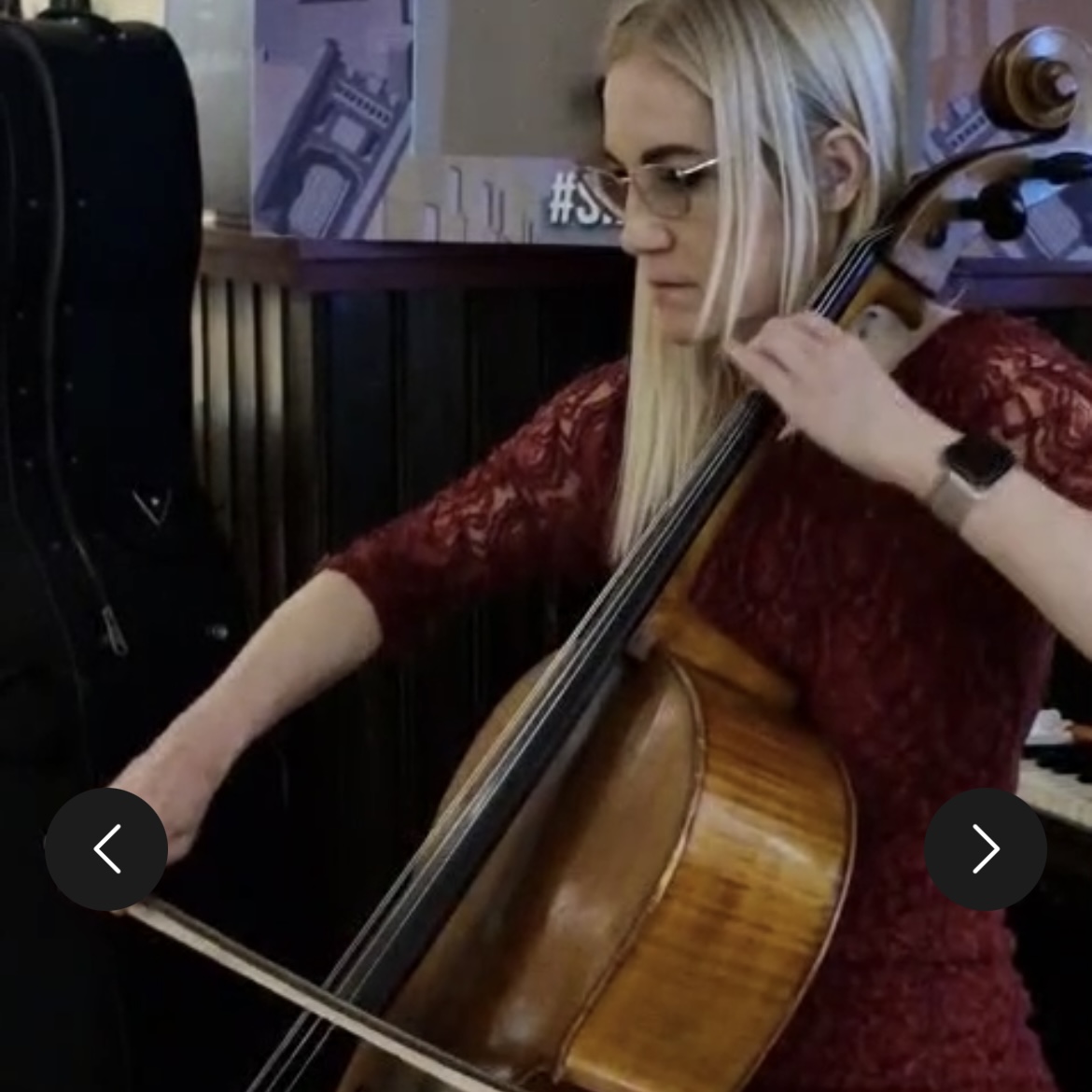

I was thinking recently about a striking similarity between two of my main passions in life, music and mindfulness, this being that both go beyond words. Then I started reflecting on why this is, and what its significance is, to me.

And it’s not lost on me here that I’m using words to describe what they themselves cannot describe.

It seems obvious to say that many embodied experiences transcend what words are capable of. Take physical pain as one other example. And is it because these things reach us before the mind has time to interpret them? Then I began wondering: is it just beyond words, or is it, in some cases, beyond cognitive understanding altogether?

Music as a Way In

Music offers us a good way into exploring this: music theory training offers us a terrain to understand musical language in terms of note lengths, note values, articulation and so on.

These are essential for the traditional learning of instrumental playing, and yet however sophisticated a grasp of music theory we might have, it can never replicate the emotion we feel listening to JS Bach, and how doing this evokes something within us that perhaps remained dormant for a while.

This bypasses the conceptual mind.

Concept vs Experience in Mindfulness

Exactly the same thing can be said of the limitations of holding a cognitive understanding of mindfulness when compared to the experiential component. However great a grasp of neuroscience someone has, they aren’t going to know what is only possible through presence, sensation, tone and body… that which can only be sensed directly.

These experiences refuse to be captured by language, no matter how detailed our explanations or how high the level of understanding, because they’re understood by the body long before the intellect can describe them.

Music and mindfulness both perfectly illustrate this gap between concept and experience.

Why Write About This?

And why is there a need to draw attention to this?

It’s the degree to which the opposite is assumed so pervasively about mindfulness.

Working within secondary mental health care has, over the years, revealed to me how much assumption circulates about what mindfulness actually is. The assertions and references made about it are not because people have spent time with a teacher or developed a sustained practice, but rather because they’ve done a short daily exercise on an app for a while, regularly skim wellbeing articles, attended one or several workplace sessions, or heard/read enough about mindfulness to feel familiar with the concept.

These things somehow tick the box for it to be either commended or discredited based on such limited understanding.

Conceptual Assumptions vs Lived Reality

It feels remiss not to point out that the confidence of these assertions usually rests far more on conceptual understanding rather than the lived experience of mindfulness.

As valuable as conceptual familiarity is, it barely scratches the surface. For something so important, vast and fundamental to our existence as awakeness, awareness to our experience and to life, this feels somewhat of a tragedy, a wholesale ‘dumbing down’, inappropriate for something so sacred.

The healthcare system, and the culture we live in at large, leans heavily on information: we read, we analyse, we learn frameworks. But the qualities that mindfulness cultivates in terms of steadiness, clarity, spaciousness, discernment, don’t arise from knowing about them. They arise only from direct contact with the experience itself.

So just as studying music theory cannot replicate the moment a Bach phrase touches us, familiarising ourselves with the idea of mindfulness cannot produce the inner shift that comes from practising it.

My Own Path and Early Perceptions

There is a parallel I can draw, not in the sense of omitting the experiential component, but in terms of how my own perception has widened and developed over the years.

My first deep exposure to mindfulness was through MBSR, which although it contains long meditations as its core content, omits much of the context of the original teachings. MBSR is a serious course requiring full commitment to the practices. This was twelve years ago now, and I can clearly see what MBSR is and what it lacks.

Only as time and my understanding progressed did I come to realise how vast its roots are, and how far beyond technique or curriculum the real practice extends. And yet I would initially have assumed my preliminary exposure to represent mindfulness as a whole. So similarity lies in the fact that we often assume our experience is the whole truth. This is an instinctive thing to do and I don’t claim to be exempt from this human tendency.

Training, Depth, and What Cannot Be Studied

I remember that as part of our teacher training, it was somewhat disparaged that at Bangor University you could attain a ‘degree in mindfulness’. This wasn’t highly regarded by our teachers, who placed precedence on the number of hours a person had meditated before allowing them onto this particular teacher training course. Without a genuinely grounded level of understanding, an embodied ability to teach cannot emerge.

Language can only, at best, gesture towards feeling what happens when the attention steadies, when reactivity eases, when the mind softens enough for space to appear. It requires sensing ourselves in real time, without needing to name, judge or control the moment. This can’t be studied, only experienced.

The high level of meditative experience required is also what allows a teacher to break things down to make them translatable and relatable to beginners in this world. We need to take what’s complex and vast and make it clear and accessible.

What My Teaching Aims to Offer

My work is now shaped by this understanding, and after years of seeing how misunderstood mindfulness can be, my role as a teacher is to help people move from thinking about mindfulness into experiencing mindfulness. To help them enter this wordless depth and achieve experiential shift, and to sense the real potential for this when we make it a lived part of daily life.

Developed as a daily habit, we can deepen it, trust it, and return to it more often in the moments that lie outside of formal practice.

This is what my course is designed to offer. We acknowledge and explore the concepts, and then step beyond them into the experience where the potential for change actually lies.

Maybe this is why I’ve always found it hard to put mindfulness into words. I hope I’ve at least brushed against what words can never fully hold.

And so, if you have any curiosity at all, I invite you to come and experience mindfulness, not just understand it.